Francine Falk-Allen Reflects on Life, Writing, and Stories That Inspire Change

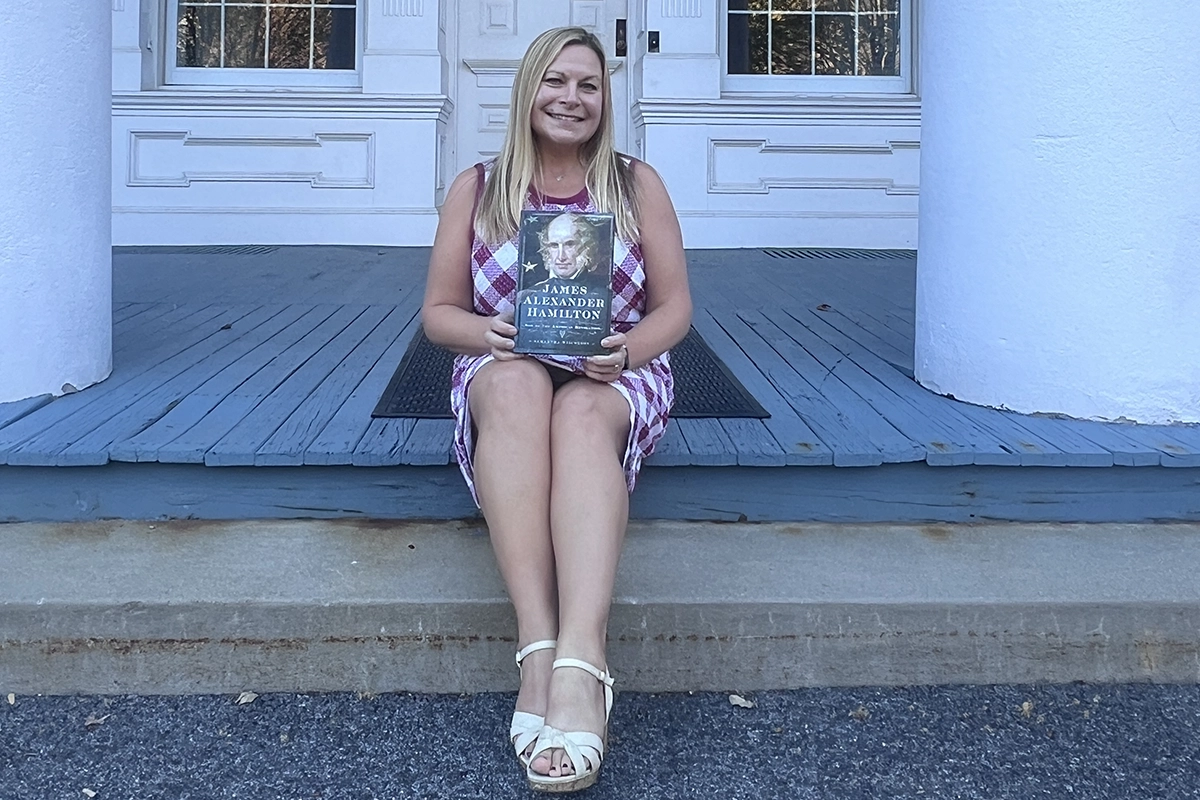

Photo: Francine Falk-Allen, author and advocate, shares her inspiring journey of resilience, creativity, and storytelling with Novelist Post magazine.

Living with Courage, Humor, and Creativity

Francine Falk-Allen discusses her journey with polio, her passion for writing, and how her stories of resilience inspire greater understanding of disability, aging, and life’s unexpected challenges.

Francine Falk-Allen is a true force of inspiration, resilience, and creativity. Her remarkable journey as an author, advocate, and storyteller radiates both wit and wisdom, offering readers profound insights into the human experience. Through her award-winning memoirs, Not a Poster Child: Living Well with a Disability and No Spring Chicken: Stories and Advice from a Wild Handicapper on Aging and Disability, Falk-Allen opens the door to a world often misunderstood, inviting us to see life through a refreshing and deeply empathetic lens. Her ability to weave humor into even the most challenging subjects demonstrates not only her skill as a writer but also her unmatched capacity to find light in the darkness.

As we eagerly await her forthcoming historical novel, A Wolff in the Family, based on the gripping real-life scandals of her family’s past, it’s evident that Falk-Allen’s storytelling knows no bounds. She moves seamlessly from memoir to fiction with the same authenticity and clarity that have defined her previous works, inviting readers into narratives both personal and universally resonant. With her dedication to raising awareness about disability, aging, and accessibility—not to mention her personal courage in sharing her own stories—Francine Falk-Allen is a celebrated voice of her generation. We are honored to bring you this conversation with her, where she shares reflections on writing, resilience, and the art of living fully.

Francine Falk-Allen masterfully blends personal experiences, historical storytelling, and advocacy for disability awareness, inspiring readers with her rich narratives and heartfelt writing.

What inspired you to turn your personal journey with polio into a published memoir?

Friends kept telling me I should write a book, based on life vignettes I had shared. When I retired, I thought, “What would I write about? What do I know well?” And the answer was: living with the aftereffects of polio. I thought it might be useful to people to know what life was like for people with ambulatory disabilities, and that their perspectives might not match reality in some ways. My perception is that many people may have the concept that disabled people are pathetic (we’re not, generally) or, not think about what we must experience in order to have a good life.

How did your background in art and business shape your approach to writing?

I have always been creative, whether it was drawing, photography, painting, or music. Writing felt like a natural extension. Early in the memoir process, a filmmaker told me I was a good storyteller, so that was encouraging. Having a head for business already was helpful in organizing the many administrative aspects of publishing, although I have found it to be less predictable and definite than the somewhat rigid characteristics of accounting!

What was the most emotionally challenging part of writing Not a Poster Child?

One of my beta readers, formerly a book reviewer, told me I was pointing my finger at people regarding how I had been treated as a disabled person. I hadn’t seen that, so I re-wrote it, told my experiences, and let the readers reflect on their own attitudes or actions. The chapter I wrote on my dad and his death and how it affected me was a tough chapter; I cried several times in the process. My father’s death had as much influence on my emotional life and my expectations of men as did having had polio. The two were intertwined.

“It will be fun to create personalities again, and do the extensive research needed to make the stories come alive!” – Francine Falk-Allen

In No Spring Chicken, you mix humor with serious themes—how do you strike that balance?

Ha! I tell people that my epitaph will read, “She thought she was so funny!” That would be especially amusing on an urn. In talking about things that people find difficult, these go down more easily—like a spoonful of sugar for medicine—if there is a lighter attitude when appropriate. Not a Poster Child also has a lot of humor in it. As Wavy Gravy (Hugh Romney) says, “If you don’t have a sense of humor, it’s just not funny.”

How did your family history influence your decision to write A Wolff in the Family?

I attended a memorial service for one of my mother’s many siblings years after she had passed. At the reception, I sat with one of my aunts, and in the middle of eating egg salad sandwiches, in one or two sentences she mentioned several shocking things I had not known about my mother’s family (nor had my sister, I later learned). One of those was that my grandfather had put my five youngest aunts and uncles in an orphanage. The reason he did this was stunning, and the things Aunt Dorothy shared seemed too outrageous a story to let lie. I was compelled to make it into an intriguing fiction.

What do you hope readers take away from your portrayal of disability and aging?

Even if you lose some function, you can still have a good life; you just have to adapt and find alternative ways of managing or find new avenues of enjoyment. Keep looking out the window. Also, for people who do not have any disability currently, I hope it will assist them in understanding how life is for those who do have impairments.

“I hear the perspectives of people who have disabilities and are aging. I can reflect in my writing common perspectives, attitudes, problems, ironies, and hopefully humor.” – Francine Falk-Allen

Can you share a particularly memorable moment from your global travels with a disability?

There have been some lovely people who have assisted me, especially in the UK, and there have been some awful things that happened, such as recently being denied boarding a plane because I did not register my scooter 48 hours in advance! That was a shock, a result of a new regulation most airlines ignore. But a farcical experience was being pushed in a wheelchair up the long conveyor ramp at Orly airport in Paris, when the attendant dumped me out on the floor on arriving at the top; he didn’t know how to lift the front wheels up over a ridge at the end of the belt. People were coming up behind us and I was piled on the floor… I wasn’t hurt, but it was like something out of a Marx Brothers movie.

How has your involvement in the ADA Accessibility Committee informed your writing or advocacy?

I would have to say that my knowledge has informed the committee more than my being with them has informed me or my writing. I was asked to join because of my lifelong disability and my experiences, which are valuable in looking at how the city will make installations or other improvements for disabled people.

What role does your writing group, Just Write Marin County, play in your creative process?

My writing group has been a great support in my accomplishment. I started the group in 2013 because I was not getting enough done on my first book. I then began dedicating a minimum of four hours a week (but usually more) to the memoir and in three or four years I had a finished book. The writers have varied over the years, but there is always a core group; we share our triumphs and difficulties and sometimes share our writing. This group was started particularly to assist in producing, for people who were either not writing enough or who wanted to write in the company of other writers.

“It helped me see that people often don’t realize that they are being ableist or saying things that might be hurtful or short-sighted.” – Francine Falk-Allen

What advice would you give to other authors who want to turn personal experiences into compelling stories?

Read, read, read, especially vibrant works. The more you read, the better your writing will be. And show, don’t tell. My editor taught me to use scenes and dialogue to make my memoir more alive and colorful, and I use that technique in most of my writing now. Characters become more vivid when we get to know them by what they do and say, not by what the author may tell us about them. I think of one popular book I started to read years ago, which in one paragraph early in the tome used the word “wonderful” twice to describe a man. I closed the book and didn’t bother reading the rest. That’s a lazy way to write! That kind of word might be acceptable if it came out of the mouth of a character; we then learn that the person uses superlatives when speaking. Lastly, employ a thesaurus to make sure you use the most specific and evocative words possible.