Randy Susan Meyers Explores the Emotional Truths Behind Family, Trauma, and Resilience Through Fiction

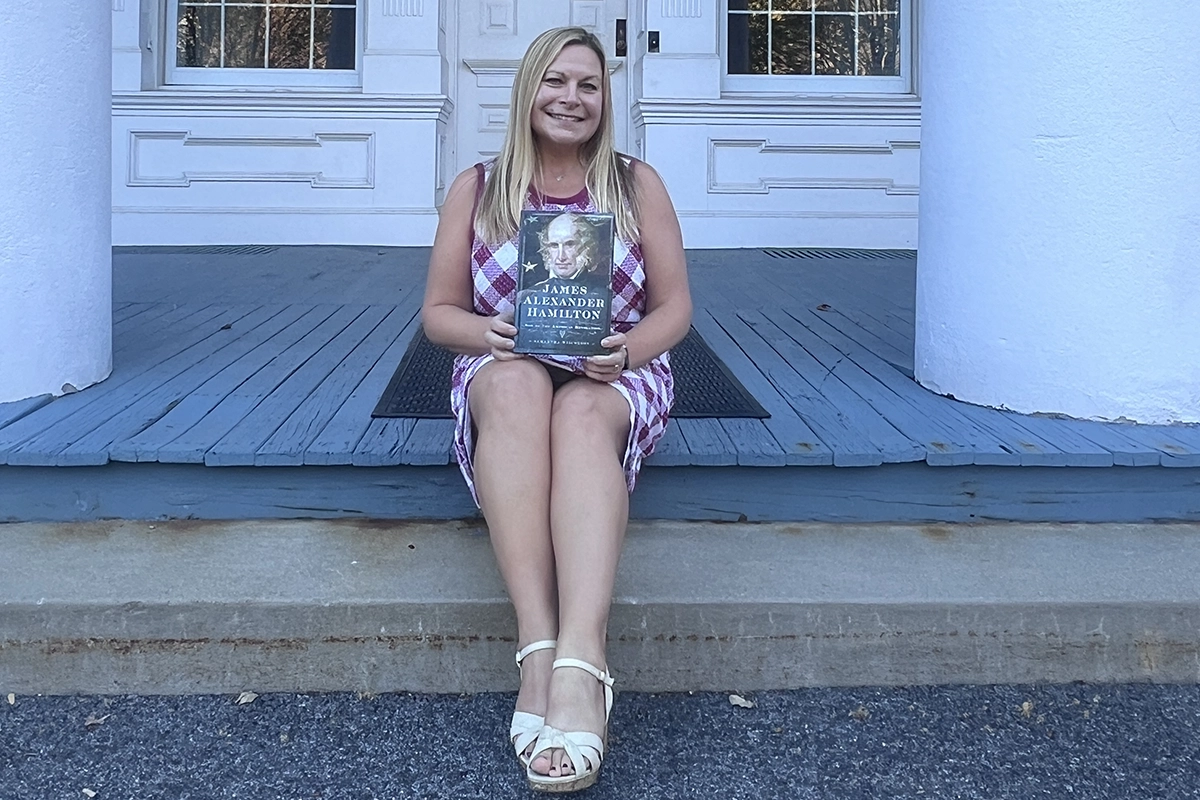

PHOTO: Author Randy Susan Meyers, whose bestselling novels illuminate the hidden truths of family and personal resilience, photographed at her home in Boston.

Unflinching Stories, Deep Empathy, Powerful Narratives

Randy Susan Meyers shares how her personal history and professional experience shape her emotionally rich novels, delving into themes of trauma, family dynamics, infidelity, justice, and the raw truths of human behavior.

Randy Susan Meyers is a literary force whose novels don’t just tell stories—they unearth emotional truths with an honesty that’s as bold as it is unforgettable. Her books navigate the jagged terrain of family, betrayal, justice, and resilience with a kind of fearless introspection that leaves readers breathless and deeply seen. With each novel, Meyers doesn’t shy away from life’s hardest questions—she leans into them, offering characters that are heartbreakingly flawed, fully human, and impossible to forget.

Through critically acclaimed works like The Murderer’s Daughters, The Comfort of Lies, Accidents of Marriage, The Widow of Wall Street, Waisted, and The Many Mothers of Ivy Puddingstone, Meyers crafts fiction that pulses with emotional authenticity. Her writing is informed by her own complex upbringing, years working in criminal justice and social services, and a deep understanding of the psychology that shapes—and sometimes shatters—our most intimate relationships.

A writer of remarkable courage and compassion, Meyers challenges readers to face the messiness of life with empathy and honesty. Her ability to combine powerful narrative with hard-earned wisdom is a rare gift—and one that continues to resonate with readers around the world. It was a true privilege to sit down with Randy Susan Meyers to talk about the stories behind her stories, the pain and purpose in her prose, and the unwavering emotional truths that drive her work.

Randy Susan Meyers writes with fearless honesty, emotional depth, and unwavering compassion, creating stories that are both powerful and profoundly relatable.

Your novels often weave together themes of family dynamics and social issues. How do your personal experiences influence the characters and plots in your books?

I had a rough childhood. My father died when I was nine; before that, my parents were divorced. Domestic violence and drug abuse were our hidden secrets.

Thankfully, I had a story-weaver in the family. Aunt Thelma. She’d transform humiliating, awful situations into eye-popping, comic-tragic tales. Her pain was our gain.

Now, life turned into stories constantly bang around my head and crowd my mind. What if? Why? How?

Besides Aunt Thelma’s stories, the Kensington Branch Library became my sanctuary, nurturing a child with an insatiable appetite for books, raised in a home with very few. Starting in childhood, I did deep dives into novels with social justice themes, with favorite authors ranging from Marie Killea to Margaret Walker and Doris Lessing. Writers were gods to me, purveyors of what I needed for sustenance: food, shelter, and books. Those were my life’s priorities.

As an adult, I still feel that way. I’m constantly foraging for books that offer glimpses into a character’s psyche, that go deep enough to make me part of the choir, saying, “Oh yeah, me too, tell it, writer. True that, uh huh.”

As a writer, I’ve learned that reaching deep enough to make the choir respond isn’t always comfortable. (My daughters will read this! My husband will think I’m portraying him!) But I want emotional truth in my work more than I worry about family opinions and push myself to write with a knife held to my own throat so that my work will be emotionally truthful.

Hey, it’s fiction, I insist.

There’s a place on my shelf for soothing books. Sometimes, I want a comfort read, a total escape, and a warm resting place. But my favorite books, the ones I return to, are gritty enough to have that emotional truth (which is very different from the truth of events).

Do writers of dreadful happenings all come from dysfunctional families? My first book, The Murderer’s Daughters, begins with two sisters who witness their father murder their mother and go on to explore the myriad ways this event shapes their lives. Did my father kill my mother?

No. But he tried. And my sister and I were there. My sister let him in (after being told, ‘Don’t open the door for your father’), and somewhere in the background, I stood, a silent four-year-old.

Did that shape my work?

Of course.

Even though it is only the first chapter that holds my family DNA close, the ongoing emotional tenor and the themes are all ripples from my past of invisibility, abandonment, and neglect.

The Comfort of Lies tells the story of three women connected by one small child: one gave birth to her, one’s husband fathered her, and one adopted her. The damages of infidelity, what being a mother means, guilt, obsession, and forgiveness are all themes I explore in this book.

Did I give a child up for adoption? No. Did I adopt a child? No. But I struggled with issues of infidelity in ways that allowed The Comfort of Lies to come alive in my mind (and hopefully on paper). Obsession is no stranger to me, nor is guilt or forgiveness.

Rage, to explosions of temper, mars too many relationships. Too many of us know by the sound of the key in the lock, the way our spouse says hello, and how our night will be. We can measure their moods by the very molecules dancing in the air around them. My novel Accidents of Marriage draws from every relationship I’ve ever had and the marriages of every friend I know.

The Widow of Wall Street? That roman à clef about the Madoff case weaves in every time I was lied to.

Waisted, centered on women’s relationship with their weight, contains the reality I’ve experienced, the fears I face every day, and my hope for the future.

The Many Mothers of Ivy Puddingstone, covering the period from 1964 to the pandemic, explores a life I might have lived (a very personal what if) had I given in to all my social justice dreams and/or nightmares. These tragedies could have been mine.

“Everyone is the star of their own show.” — Randy Susan Meyers

How did growing up in Brooklyn and your early dreams of justice and social change shape your journey as a writer?

My Brooklyn childhood was rooted in social dilemmas, though I couldn’t recognize it then. My father’s violence against my mother led to the police in our lives; he died at 35 from drug use. I escaped through incessant reading, spending most of my time at the local Brooklyn library, where I buried myself in books, always drawn to those rooted in social issues. Scholarships from a New York organization allowed me to attend a summer camp from ages six through fourteen, when I began working there.

Between being saved by attending a diverse multi-cultural camp and my self-directed immersion in novels set during the times of slavery, the Holocaust, war-torn countries, and issues of social class and poverty, my vision has been personally and professionally skewed towards fighting injustice.

Before turning to writing full time I worked in social service and criminal justice, including directing an inner-city community center (where I also lived) and working with convicted batterers adjudicated to a domestic-violence prevention program.

The Ethel and Julius Rosenberg espionage case became profoundly important to me at an early age— their execution felt like a warning.

My mother voted Democrat, though she was anything but politically active. My (beloved) grandfather’s subscription to “The Daily Worker” terrified her—something I did not understand until I was a teenager and became aware of the horrors of the ‘Red Scare’, Joseph McCarthy, Roy Cohen, and their ilk.

The Rosenbergs’ execution took place when I was barely a year old, but I conflated their case with Grandpa Bernie—the only male constant in my life—worrying about him, even though the case was in the past.

What if the mysterious “they’ took away Grandpa? What if they executed him?

I learned more about the Rosenberg case when I read “We Are Your Sons” by Robert and Michael Meeropol, the first hardcover book I ever purchased. Many years later, kismet led me to a friendship with Robert and Ellen Meeropol (his wife)—I devoted the funds from my latest book launch to the Rosenberg Foundation for children.

How do you navigate writing about difficult topics, such as domestic violence and infidelity, while ensuring authenticity and empathy in your narratives?

I believe the best fiction is page-turning and nourishing, building and evoking empathy while providing entertainment. When writing, I stay very close to my characters—virtually becoming them as I write. I experience the tragedy, hope, love, and hate with them.

Perhaps I draw on my childhood—not only for the hardships I had but also for one of my methods for dealing with those problems. When forced to turn the light out (not being able to read anymore was true punishment to someone who lived through her library books), I built stories in my head, and of course, they were strange and wondrous adventures in which I was the star.

Now, when I write, I ‘build’ the characters, and though they aren’t me, they all hold a piece of me (for instance, the crooked character has a piece of the eleven-year-old me caught shoplifting in Woolworths), and I enter their world fully.

Working with criminals for over ten years, I learned an important lesson: everyone is the star of their own show. And everyone finds a way to excuse their worst behaviors. I work hard not only to become my point-of-view characters, but to believe in the worlds they create in their mind.

“Writing fiction is the only place and time in this world when I just let it rip.” — Randy Susan Meyers

In your author’s note for “The Many Mothers of Ivy Puddingstone,” you mention exploring the limits of familial love. How do you balance crafting complex characters with relatable familial themes?

Family themes are relatable because, below the shiny surface (if there is one), all families hold secrets, though most may be more intense than the ones in our families. People love reading to be swept away and to explore other worlds, but also to sink into ‘there, but for the grace of God, go I’.

Underneath the covers of our lives, we are all complex creatures—but some of us are far better at hiding than others. Reading allows us a glimpse of the interior lives of others—warts and all—a journey into other’s lives we crave.

The writing rules I try to follow to write interesting books are these:

- Make things as difficult as possible for my characters. (This is hard; we tend to fall in love with them as we write them!

- Show the ickiest thoughts and feelings they have. This offers the reader either a wow of

‘She’s thinking what I fear saying,’ or, ‘Whew, at least I’m not that bad!’ - Surprise the reader with radical honesty from the characters.

“The best fiction is page-turning and nourishing.” — Randy Susan Meyers

Your books are praised for their emotional depth and truth. Can you discuss your writing technique for achieving this level of emotional authenticity?

Early on, I fought to get the ‘reader off my shoulder.’ There is always that fear that your mother, sister, daughter, husband, son, cousin, and every friend will read it and think it is you. This fear keeps many of us from writing as rawly as possible.

We all suspect the writer is revealing herself, even when she’s not. They might think you are a secret crook, murderer, embezzler, adulterer (etc, etc!). So, I gave up trying to ‘hide.’ I know my characters aren’t me, even if they hold bits of my DNA and reality (warped into fiction.) My work is to give the reader the very best possible ride. That’s what they deserve. That’s what I want when I read. Writing fiction is the only place and time in this world when I just let it rip.